When I was a boy, I used to sit down at the piano and puzzle out how to play the melodies I was hearing on the phonograph, on the radio, or in church. The Greek Orthodox hymns sung as part of the Sunday service (the Divine Liturgy) are repeated every week (with some variation, as prescribed by the calendar) so the melodies become familiar after years of church attendance. They are pretty simple melodies, which makes them easy to remember.

Some hymns are reserved for special occasions, such as a memorial service, when we remember and pray for the dead. This occurs at a funeral, and immediately after the Sunday Divine Liturgy forty days after someone has died, a year afterwards, and beyond that whenever the family wants to have a memorial service. Children always can tell when a memorial service is happening: First, we get a delightful treat called koliva (a special food prepared to be shared after a memorial service, which consists of wheat kernels, parsley, powdered sugar, and often nuts and pomegranates). Koliva has a history – originally, it was fed to a group of Christians to help them avoid eating defiled food during a fast. Second, the service includes some special hymns that are sung only on that occasion, and when a little boy hears those, he knows it soon will be time for koliva. The image of wide-eyed children scarfing down this special treat after a service for the dead is a vivid reminder that death is an illusion.

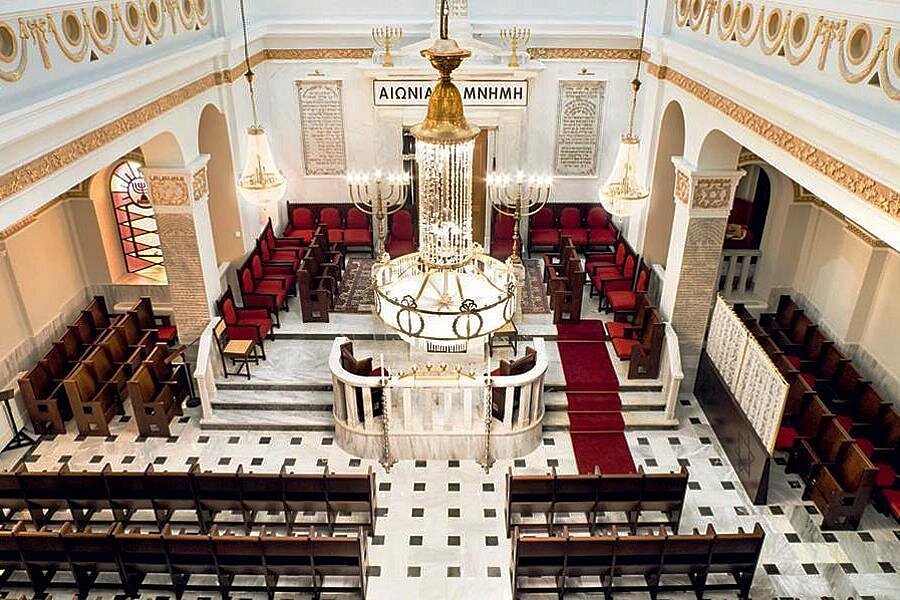

The most memorable of the memorial service hymns is Eonia I Mnimi (“Eternal Be His/Her Memory”), which is sung at the end of the service, and unlike most of what is sung during the service, it is written in a major key. I remember one day I was sitting at the piano playing that melody and singing along with it (the lyrics are simple and repetitive, so even a child can memorize them easily just from hearing them in church). My Mom came into the living room to stop me. “Please don’t sing that. It’s morbid.” I guess some people don’t want to think about death a lot, and I do get why that is, but I’ve never been one of them.

Music and death, after all, are closely connected, as partners and as opponents. They are partners in the sense that death gives occasion and emotional inspiration for music, but opponents because music is an essential part of how we transcend the darkness and loss that accompany death.

Evidence that they are partners abounds. Can anyone deny that two of the most powerful pieces in the classical canon are the requiems written by Mozart and Brahms? Verdi’s first big hit, the choral piece, Va Pensiero from the opera, Nabucco, was written in 1842, just after the deaths of his wife and children. Its subject is the aspiration of Hebrew slaves during the Babylonian Captivity to return to their homeland. It resonated at a time of heightened national ambitions for Italy and was Verdi’s most beloved choral work. At his death, people in Milan's streets spontaneously sang Va Pensiero as his funeral procession passed, and a month later, when Verdi was reinterred alongside his wife, Arturo Toscanini conducted a choir of eight hundred singing it.

The dependence of humans on music at moments of grieving is timeless. The oldest music still performed in Greece are the mirológia from the musical tradition of Epirus (pronounced in Greek Ípiros), which is pre-Homeric. The word mirológia literally means “words of fate.”

Mirológia are lamentations performed when someone dies, but interestingly, the musicians from Epirus perform and record mirológia quite a bit, so that one can experience them apart from occasions of grieving (I guess my Mom would not have approved). Some of those performances are instrumental, some are vocal. The instrumental versions tend to feature the violin or the clarinet, which are the most important local instruments. The ethnomusicologist, Christopher C. King, has written a wonderful book about this tradition entitled, Lament from Epirus. Alexis Zoumbas is perhaps the most famous of the violin virtuosi of this tradition, and it is not hard to find his playing online. Most Greeks don’t find these sounds familiar, or even pleasant to listen to. I love them, but they are perhaps an acquired taste.

There is an intense need for music at times of loss. These are moments of spiritual clarity when we are ready to let powerful sounds resonate within us, when we want something meaty to listen to (not the typical drivel), when we are willing to make space and time to actually listen.

Music can help us transcend loss and death, as a group of people, and even as a nation. There are two important historical examples of that transcendence that I often think about. Both occurred during World War II. World War II, after all, was a time when people relied on music so much in their struggle against darkness. Consider the scene from the movie, Casablanca, when the clientele at Rick’s Café spontaneously erupt into The Marseillaise as a way to express their common humanity in the face of Nazi dominance. My two real world examples from World War II have much in common with that fictional one.

Readers of Ákou are already familiar with the great rebetiko composer and bouzouki player, Vassilis Tsitsanis. The first example from World War II of the power of music to defeat death and darkness is connected to one of his songs, called “Cloudy Sunday” (Synnefiasmeni Kyriaki), which has sometimes been described as an unofficial national anthem of Greece.

Rebetiko music found its moment during World War II partly because it had always been associated with non-conformity and resistance to authority. Cloudy Sunday, on its face, is just a melancholy love song about an unnamed love that the singer has lost. Although it is a mournful song, interestingly (like Eonia I Mnimi) it is written in a major key, which I think gives it a triumphal feel. The lyrics point to the Sunday when the singer lost his joy, a Sunday that makes his heart bleed. The song was written during the German occupation of Greece and worked as an anthem of resistance because it appeared to be only a love song, but was in fact understood by the Greeks to be about (in Tsitsanis’ words) “the tragic incidents that happened then in our country: starvation, misery, fear, depression, arrests, executions.”

Another aspect of this sort of rebetiko music that is worth mentioning, which is true of Cloudy Sunday, is its rhythmic structure. The song is in 4/4, and the rhythmic pattern of this type of song often emphasizes two consecutive eighth notes at the beginning of the measure, and another two consecutive eighth notes beginning just before the third beat of the measure (so that the second one lands on the third beat). If you clap that structure, you will see that it is conducive to defiance. One dances to it with an erect posture. To me, this is the brave rhythm of resistance, a rhythm with which to face even death.

The second example of death-defying music from World War II is a story from the Nazi death camps. In his monumental memoir of Auschwitz, Primo Levi wrote about the ways that maintaining simple daily routines preserved individual dignity in the camp (Lager):

…precisely because the Lager was a great machine to reduce us to beasts, we must not become beasts…to survive we must force ourselves to save at least the skeleton, the scaffolding, the form of civilization. We are slaves, deprived of every right, exposed to every insult, condemned to certain death, but we still possess one power, and we must defend it with all our strength for it is the last – the power to refuse our consent. So we must certainly wash our faces without soap in dirty water and dry ourselves with our jackets. We must polish our shoes, not because the regulation states it, but for dignity and propriety. We must walk erect, without dragging our feet, not in homage to Prussian discipline but to remain alive, not to begin to die. (Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz, New York: Touchstone, 1996, p. 41).

Levi saw the Jews from Thessaloniki as unique:

…those admirable and terrible Jews of Salonica, tenacious, thieving, wise, ferocious and united, so determined to live…those Greeks who have conquered in the kitchens and in the yards, and whom even the Germans respect and the Poles fear...They now stand closely in a circle, shoulder to shoulder, and sing one of their interminable chants…And they continue to sing and beat their feet in time and grow drunk on songs.

….their aversion to gratuitous brutality, their amazing consciousness of the survival of at least a potential human dignity made of the Greeks the most coherent national nucleus in the Lager, and in this respect, the most civilized. (p. 79)

A central purpose of culture, I suppose, is to empower individual humanity, to give us a storage chest of songs, sayings, tastes, images, and dance steps that we can draw upon as the moment requires, to affirm our humanity.

I remember reading, at the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki, about one of those groups of Thessalonian Jews at Auschwitz, facing their end, knowing that they were about to be gassed, who broke out in song together one last time, singing until death the Greek national anthem. Standing powerless and about to die, they demonstrated what it meant at that moment to be Greek and Jewish, and what it means for all of us to confront death with music and humanity. In the process, they made that moment of their lives forever sacred for all people.

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)