Today’s world is dominated by secular thinking. Scientific discoveries have displaced many superstitious beliefs, and most people—especially the highly educated—scoff at the idea that God performs miracles. But miracles shouldn’t be equated with antiquated superstition. For the faithful, miracles are understood as events that reflect God’s ability—and choice—as Creator to intervene in His world, as part of His divine plan, and sometimes in response to prayer.

If God exists, and if He has a plan for us, why wouldn’t He occasionally perform miracles? When people dismiss the possibility of miracles, what they really mean is that they reject the existence of a personal God—a being who created the world with a purpose and who has a plan for humanity. They also reject the possibility of a reality beyond the physical one we observe, the world that reliably conforms to the principles discovered through science.

But those rejections aren't based on scientific evidence. Science and faith are not substitutes; they are complements. As the great scientist Werner Heisenberg famously said: “The first gulp from the glass of natural science will turn you into an atheist, but at the bottom of the glass God is waiting for you.”

I freely admit to believing in miracles, despite my over-educated background and long-standing membership in the secular elite (I’ve been a professor for over forty years). My belief is empirical: I’ve witnessed phenomena that I cannot satisfactorily explain in any other way. Now, I’m not saying you wouldn’t be able to explain these events differently. We don’t share access to the same information—my observations include personal experiences that, by their nature, cannot be directly observed by others. I don’t blame anyone for being skeptical of my testimony.

In fact, I believe God deliberately makes miracles difficult to prove to third parties. If miracles were easily demonstrable to everyone, where would be the need for faith? Recall that Jesus performed miracles in response to faith, and rarely used them to inspire belief. That’s why He didn’t perform miracles in Nazareth, and why He often told those He healed to keep it to themselves.

So, when I share an experience that I hope some of you might find interesting, I’m not trying to persuade you that miracles exist—that would be a fool’s errand. I’m simply sharing the unusual backstory of how one of my songs was written. You can make of it what you will. But to tell the story truthfully, I must admit that I believe I experienced a miracle.

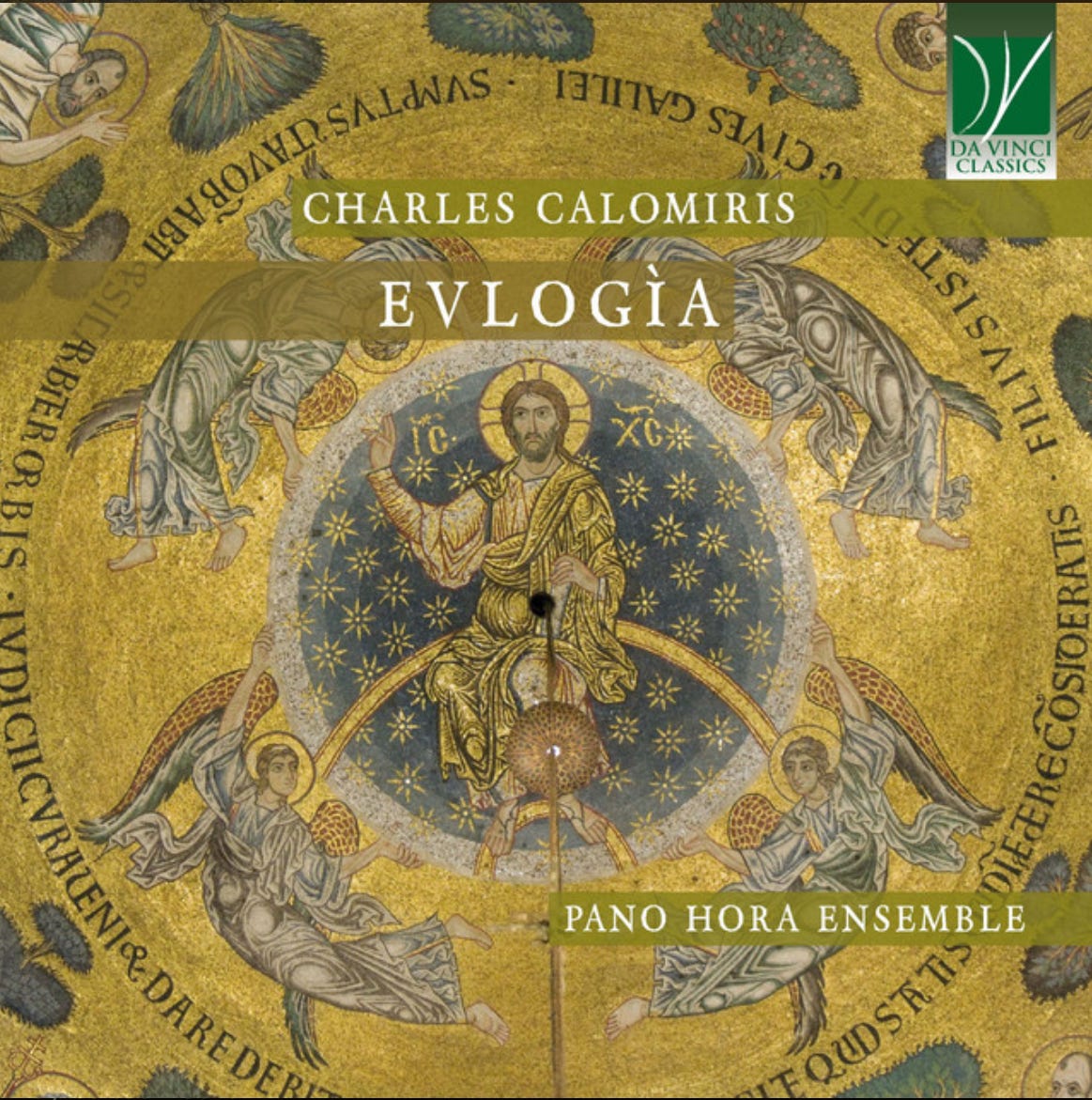

While composing the album Evlogía, I wanted to write something about King David and the Book of Psalms. There were many reasons. Most obviously, the Psalms are the most musical part of the Bible, and their verse structure offers excellent material to draw from. They also possess profound emotional depth, and David’s life story is itself full of powerful emotion—making the Psalms perfect for the purpose of Evlogía (see the nearby blog entry, “Why I Wrote Evlogía”).

The Psalms also highlight what made Judaism distinct from the pagan worship of the contemporaneous Greek world. A defining feature of Judaism is the personal relationship it envisions between God and each person. Yes, in The Odyssey, Odysseus and Telemachus have personal relationships with Athena—but those relationships are nothing like David’s with God.

Athena did not create anyone, nor is she bound to any moral standard. In contrast, God is David’s Creator and holds him (and all of us) accountable to established moral laws—the Commandments—that define sin and virtue. God loves David, and when David commits sins, God provides a clear path to forgiveness. Unlike Athena, who offered strategic counsel to heroes, the God of David creates, loves, and forgives. David’s relationship with God is personal, moral, and redemptive—anchored not in myth but in covenant.

Because David was created by God, he has imprinted in his being an inherent need for God and a love for him. The theologian, St. John Chrysostom, describes this longing for God as Eros. David illustrates it when he says that he “thirsts” for God. This divine imprint also enables each of us to recognize truth when we hear God's Word, forming the basis of faith and helping us to return to God after we have strayed.

When writing a song, some songwriters begin with lyrics and then craft a melody, while others—like Paul McCartney, by his own account—usually start with the music. In practice, the process often becomes a back-and-forth refinement between words and melody.

I usually start with lyrics. But not with King of Heart.

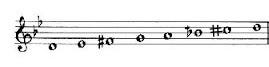

I wanted to compose something in the Anatolian Hijaz Kar mode, which is also known as the ancient Hebrew Ahava Raba mode, used in certain sacred contexts. I hoped to capture the yearning and emotional intensity found in many Psalms—qualities this mode is especially suited for. Thinking of David and his story, I sat down with my bouzouki. A melody in two parts came to me unusually quickly—before I’d had a chance to think about lyrics.

But which psalm—or psalms—would fit this melody? How would the verses align with it? This is why I normally begin with words.

Then I had an idea: perhaps the song could be about David’s decision to pray through music—about music’s role in his prayer life, and its unique ability to add emotional depth to prayer. I pulled out my Bible and read through the entire Book of Psalms, writing down every line related to music or sound. I transcribed them in small print onto a single sheet of paper, more or less in the order they appeared.

By the end, I had a full page of individual lines about music. Now what?

What happened next is something of a blur, compressed into what felt like just five minutes.

Each line seemed to leap from the page into its place within the melody. The sequence made perfect sense. When I was done, I looked at the lines I hadn’t used and realized that no important theme had been left out.

Of course, one could say that all musical composition is miraculous—and I’m open to that idea. But what happened while writing King of Heart went beyond anything I’ve previously experienced. Make of it what you will—but I honestly cannot explain how it happened.

David prayed with strings, not just words. In his Psalms, music became theology, and melody became prayer. Some moments of composition feel less like invention—and more like revelation.

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)