From left to right; Tylor Thomas, bassoon; Ginevra Petrucci, flute; Michelle Farah, oboe; Kai Hirayama, clarinets.

On October 11, 2025, the Pano Hora Ensemble is presenting our next concert, which will feature our wonderful woodwind quartet, accompanied by our percussionist, Oliver Xu. Further details about the performance will be published in this blog in due course as we get closer to the date. But that upcoming performance makes this an especially good time to reflect on the contributions of our four woodwind players to the Pano Hora Ensemble.

According to Proverbs 11:29, “he who troubles his own house shall inherit the wind.” It’s one of my favorite proverbs, partly because I have witnessed an example or two of it, but those are stories for another day. Today’s wind tale is a happy one, in spite of such a tragic Proverbial reference. Let me tell you about the woodwind quartet that lives within the Pano Hora Ensemble and the strokes of good fortune through which I came to “inherit” them.

Just before the Covid epidemic hit New York, with the talent scouting assistance of my friends, Godfrey Furchtgott (an extraordinary guitarist, violinist and recording/mixing engineer) and the brilliant violinist and conductor, Daniel Zinn, I got to meet many talented musicians living in the New York area. We started experimenting with recording chamber music for various classical ensembles. Some of those early experiments ended up on the Pano Hora Ensemble’s first album, Songs from the Lost and Found – a title well-suited to the variety of styles and instrumentations in the album, which reflected the undisciplined and experimental process of writing and recording whatever popped into my head.

At the first of the rehearsal sessions, I was conscious of my inexperience in writing music for a classical ensemble and my ignorance about the idiomatic qualities of the various instruments involved. I was scared that what I had written probably would stink and that the musicians would laugh at how bad it was. Instead, they did what I have learned to expect these musicians to do: they encouraged me, not with compliments – by the way, I could use even a phony compliment from time to time, in case anyone wants to give me one – but with constructive suggestions that showed me that they took my efforts seriously and were willing to help me make the music better.

In the piece, Evening Stroll , which was written for a woodwind quartet – buttressed at the very end by a trumpet and trombone – the bassoonist, Tylor Thomas (now the editor of this blog), pointed out to me that I could achieve more variety by expanding the range of the bassoon part, and he had specific helpful ideas about where to do that. Ginevra Petrucci, the flautist, helped me figure out how to notate the trill I wanted (and helped me pick which trill to use). All of them, along with Daniel Zinn, helped me work through the dynamic phrasing of each section and the articulations of each note.

Later, at another session, when we recorded the two Peloponnesian dances I had written (for flute, clarinet, violin, bass, and guitar), I commented on how beautiful their playing was, and how much it meant to me to hear the music I had written played so well. Ginevra just said three words, with a smile: “We get you.” In that session, when Daniel Zinn thought to raise the flute part by an octave in one spot of the piece, Taygetos , Ginevra noted that doing so would work better on a piccolo, but then said, “if we must, we must,” and of course, it sounded wonderful on the flute. I wondered, “Is Ginevra really Mary Poppins?”

There is a random aspect to finding a quartet of wind players who are particularly suited to each other, musically and personally. Over time, oboist, Michelle Farah, and clarinetist, Kai Hirayama, became regulars in the woodwind section alongside Ginevra and Tylor. I remember asking Michelle how she managed to avoid the “honky” sounds that sometimes occur in the low register of the oboe, to which she replied: “Practice.” And then: “Thanks for noticing.” And from the first piece Kai played with us, I knew he would add something special (in addition to technical brilliance) because he was willing to experiment to see if he could make things better. And it didn’t hurt that he was familiar with the traditional Greek stylistic approach to the clarinet, which I often employ in my compositions.

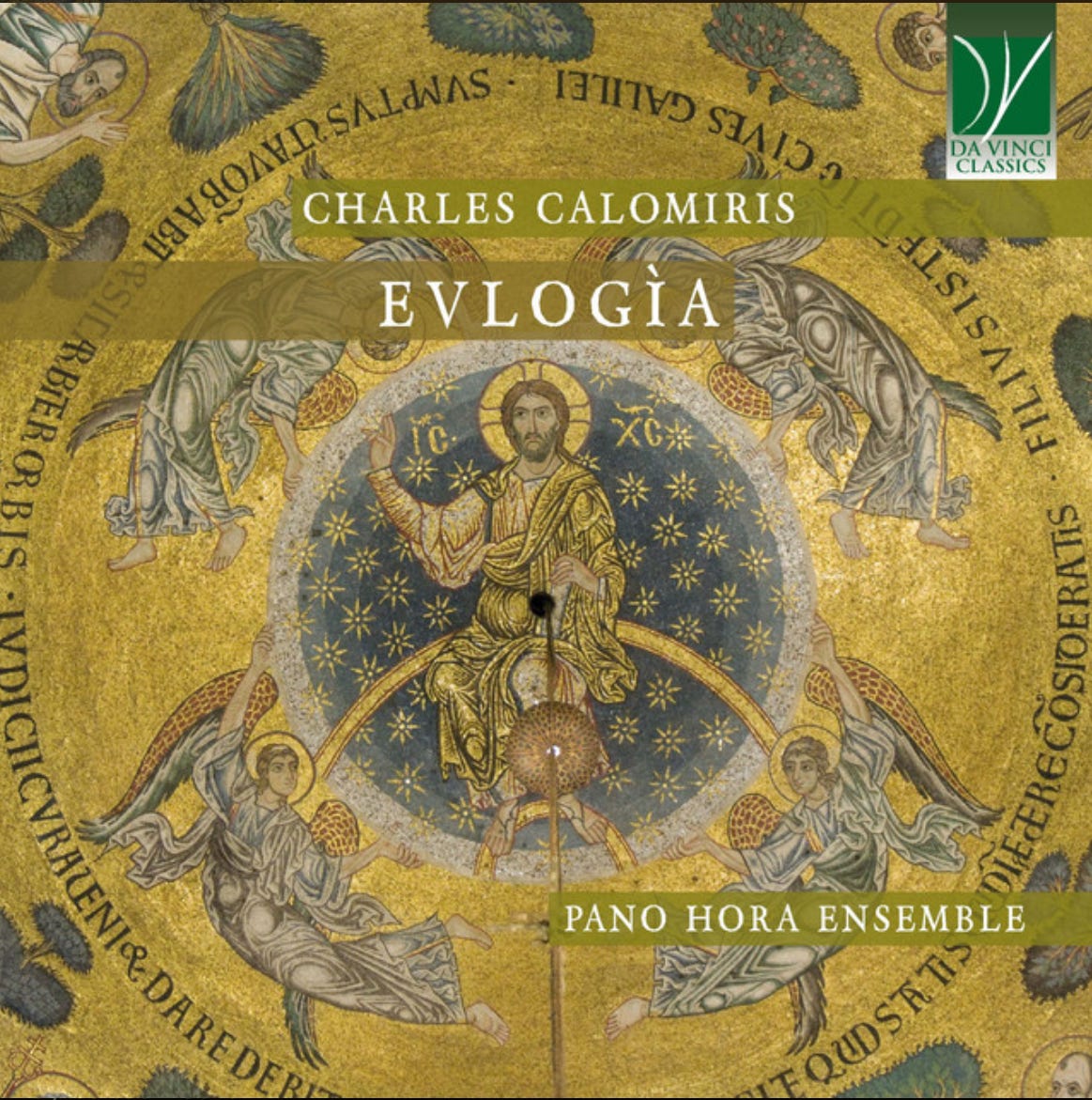

How did I get so lucky? I don’t know. But I do know that this specific history had a major effect on the evolution of the Pano Hora Ensemble. If you look at the tracks on the three albums that we have already published, you will notice (1) that the flute appears more frequently than any other instrument, (2) many of the pieces are written to include the woodwind quartet, and (3) there is lots of solo work for each of the four woodwinds (Oboeliks , which features the oboe, makes use of an instrumentation led by oboe that I have not seen before). In our most recent album, Evlogía , there are three tracks that feature only the woodwind quartet (sometimes with percussion added) – Styx and Sto

nes , Blessed , and Eleftheria . In our forthcoming recordings of Gethsemane and Concerto Grosso Laїko , you will see the same emphasis, including solos for each of the four woodwind instruments in each of those pieces. This woodwind focus was largely an unconscious and natural “path dependence” – it’s easier to write parts imagining sounds akin to the ones you have been hearing and loving.

Inheriting the Winds

September 12, 2025

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)