If you know me, you know I have a thing for Greek lutes. I’ve been playing them since I was a boy, and I keep acquiring new ones (just ask my wife, Nancy). I’ve met several others with the same lute-hoarding affliction, by the way—Ara Dinkjian and Theo Drivas, you cannot hide.

I recently wrote about my visit to the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, which had a profound effect on me, partly because of the hundreds of lutes on display—many of which I’d never seen before (luckily for Nancy, none were for sale).

So, you might think today’s topic is a psychoanalysis of lute hoarders like me (or Theo or Ara). It’s not. Today’s subject is the incredible variety of lute types—and what we should make of it.

The list includes the oud, the Western lute (and its many offshoots and predecessors), the Chinese four-stringed pipa, the so-called long-necked lutes—such as the trichord bouzouki, the tetrachord bouzouki, the Greek baglama, the Greek dzouras (or tsouras)—the many varieties of mandolin, and the laouto. (And I’m not even getting into the vast array of related instruments in the Persian, Indian, Turkish, and other traditions.)

Lutes typically have rounded backs and double-stringed courses (although the pipa is an exception). Regarding the doubled strings, I’d speculate that their appeal lies in the complexity and richness of sound they produce. No matter how closely two strings are tuned, they’re never perfectly identical—which adds a subtle, textured quality to each note.

Despite some common features, lutes differ dramatically in fundamental design. Some have frets, others don’t. The number of strings, types of strings, and tuning systems all vary widely. Even within Greek music, the differences between lute types are substantial—so let’s focus on those.

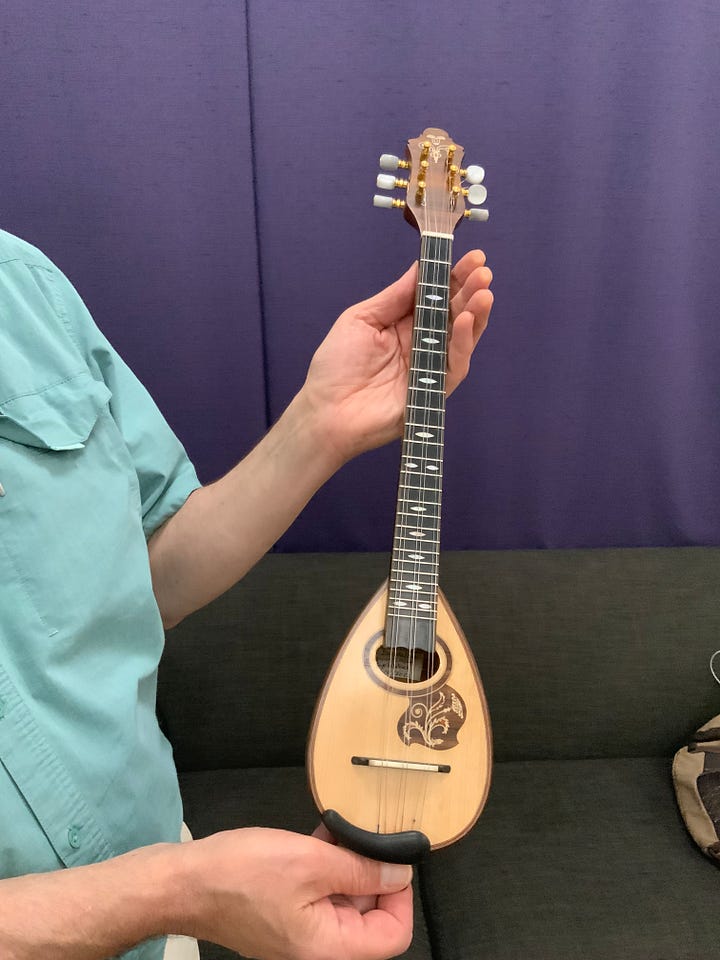

The baglama, dzouras, and trichord bouzouki are all fretted, with three courses of double strings typically tuned D-A-D, but they operate in different registers (the baglama is pitched higher). The tetrachord bouzouki is also fretted, but it has four courses, tuned in intervals similar to the four highest strings of a guitar (C-F-A-D). My baglama is below:

The oud has no frets and eleven strings—five double courses plus a single low string. Most string pairs are tuned in fourths, though tuning can vary between Anatolian and Arab traditions.

The mandolin is fretted and tuned in fifths, like a violin. The laouto, also fretted, typically has four courses of double strings tuned C-G-D-A—again in fifths—but with movable frets.

Mandolins and ouds double the same notes in each course, while bouzoukis, dzouras, baglamas, and laoutos use a mix of identical and octave-paired strings (e.g., D3 and D4).

Most lutes have a single soundhole, but ouds typically have three. Long-necked lutes and mandolins are played with picks, but the oud and laouto use unique plectrums.

String materials also differ. Steel strings—introduced around the turn of the 20th century—are used exclusively on bouzoukis, dzouras, baglamas, and mandolins. Laoutos and ouds, like classical guitars, often combine steel for low strings and nylon or gut for higher ones.

Why all this variety? I’d suggest two main explanations:

- Musical considerations—different instruments produce different sounds.

- Cultural influences—changing tastes determine which sounds are considered desirable.

The first category is more obvious. Gut strings on an oud sound softer than steel strings on a bouzouki. Multiple soundholes (as on an oud) affect resonance. The surface area of the top also matters: less area means less resonance (as with a dzouras compared to a bouzouki).

A higher register, like that of the baglama, does more than just raise pitch—it changes the instrument’s role in an ensemble. The baglama can play higher melodies and also perform “clinky” chords that aren’t as easily played on other instruments (due in part to narrower frets). This can give it a kind of pitched-percussion role.

Due to its small size, the baglama was also reportedly used by inmates in Greek prisons—perhaps because it could be easily concealed, or because only small instruments were permitted. Given the prominence of prison life in rebetiko lyrics, this history might be more relevant than it first appears.

Consider the famous song by Apostolos Kaldaras, Mou Spasane to Baglama (They Broke My Baglama):

They smashed up my baglama,

Some wise guys, yesterday late at night,

They smashed it up and left,

I was left just with the strings.

Trinka trinka trinka trinka,

It took away my pain.

Trinka trinka trinka trinka,

And life goes on.

Why use both trichord and tetrachord bouzoukis? Manolis Chiotis developed the tetrachord in the 1940s. Many players, like me, still prefer the trichord because it encourages more horizontal playing (moving down the neck). But I’m told that for long gigs, the more vertical finger movement required by the tetrachord can save energy—making it easier to play well for longer.

The second category of explanations for lute variety—cultural influence—is especially important for understanding the use (or avoidance) of frets. Fixed frets reflect both a commitment to Western well-tempered tuning (which is a compromise tuning that deviates from “correct” pitch) and a restriction to half-step intervals (C to C# to D, for example).

Well-tempered tuning means the frequency of a note like C is not permitted to change slightly depending on the key. On a fretless instrument (like an oud or violin), players can adjust intonation depending on the key. On a fretted instrument (like a bouzouki or guitar), they can’t.

Traditional Greek music often uses microtones—notes between the standard Western half steps. For example, one of the two major scales used includes a Pythagorean major third, slightly different from the one found on a piano or guitar. Fretted instruments can’t naturally access those tones—unless their frets are movable, as on the laouto.

Movable frets offer flexibility, but to an accomplished oud or violin player, they may seem unnecessary—and frets can hinder techniques like sliding.

Interestingly, there’s been a historical ebb and flow in Greek music between fretted and fretless lutes. Before World War I, the oud dominated. Between 1920 and 1950, during the rise of rebetiko music in Greece, the bouzouki (and to a lesser extent, the baglama and dzouras) took center stage. Since the 1990s, there’s been a renewed interest in the oud.

I asked Ara Dinkjian if he had any theories to explain this shift. One idea he shared is that perhaps after WWI Greece may have sought to emphasize its European identity—embracing Western musical systems and fretted instruments. Later, with more cultural confidence (or nostalgia), musicians began rediscovering older modes and instruments—leading to a revival of the oud.

That theory highlights that musical instruments reflect not only our aesthetic preferences but also our identities—personal and cultural. Like us, they evolve over time, shaped by who we are, what we value, and how we want to sound.

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)