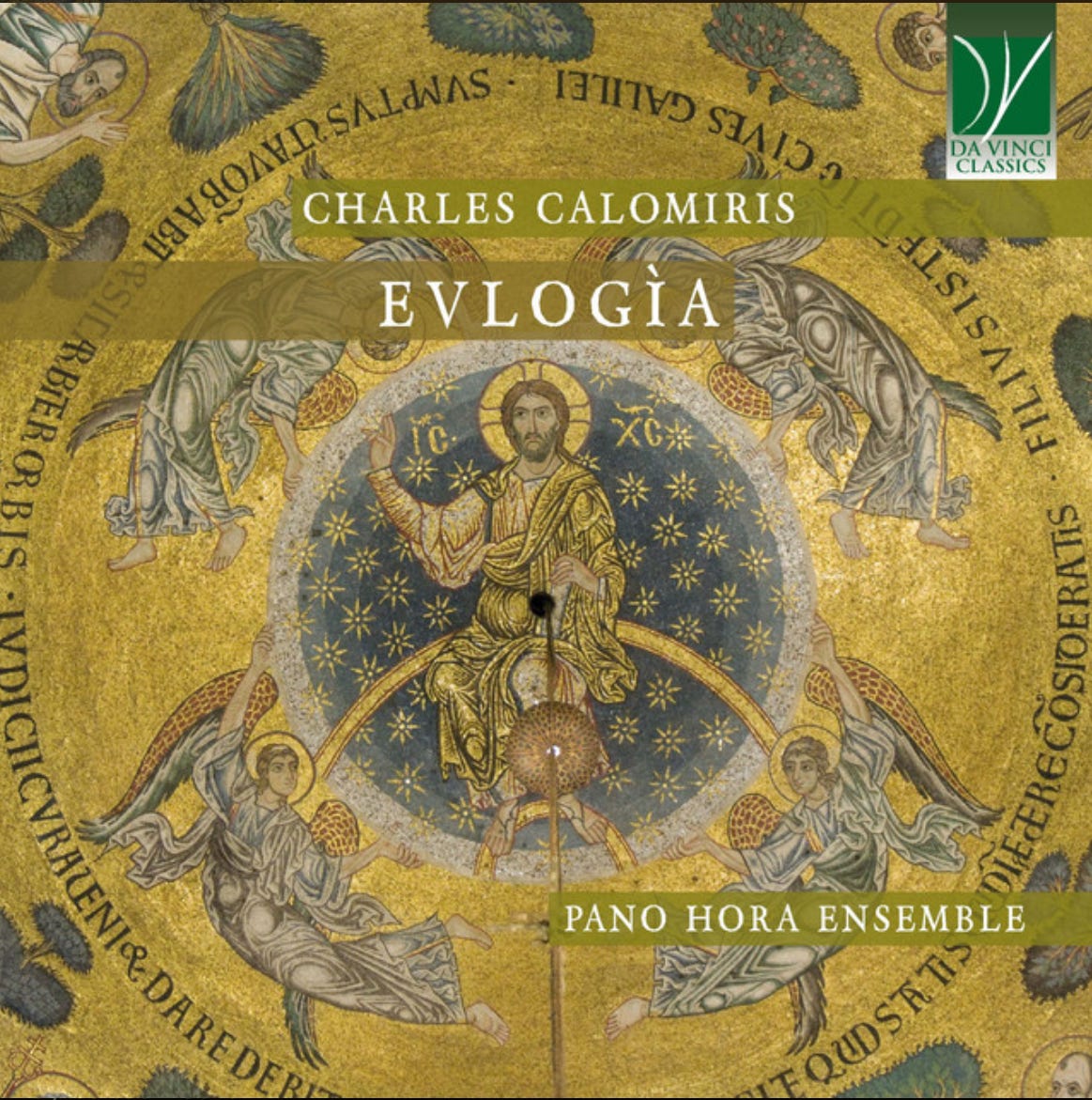

Michael Haldas’s poems take on big issues and are infused with spiritual content. The same can be said for his podcasts and his theological writings. Michael’s poems appear as lyrics in four of the tracks on the Pano Hora Ensemble’s recent album, Evlogía. In this interview, Michael tells Ákou! how he began writing poetry, describes the process he follows when doing so, and explains how he sees the connections between art and faith.

Charles: Thanks so much for agreeing to meet, Michael. Let’s start by talking a bit about your childhood. You grew up in Wilmington, Delaware and in Philadelphia, right?

Michael: I did. My grandfather came from Greece and started a butchering business. It was Haldas Brothers Meats, which started in the Philadelphia area and then moved to Wilmington where it was famous for years.

I grew up working at various places that were part of my grandfather’s and father's butcher business, and at my uncle's produce business. It was a very blue-collar upbringing. But I always had a strong desire to be a writer. And I wanted to be involved in the arts, more generally. That really wasn't part of our family dynamic and they didn't seem to understand it.

I felt the need to move to the DC area. I had some relatives in DC and I was very enamored and impressed with it. If I had to give a color to the area I grew up, it was gray. But DC seemed red and vibrant.

After college, I landed a job with a DC company I'd worked for in the summer as a technical writer. One thing led to another, and I've been here ever since.

Charles: I grew up here in DC but always looked at Philadelphia as the more interesting place. I guess the grass is always greener…

Michael: One of the things I miss about Philly is the local flavor of things. For example, there are lots of local pubs and locally owned restaurants and there’s an older quality to it, which I didn't quite appreciate until I came to a new place. I also very much love the Brandywine Valley area that is in both Delaware and Pennsylvania. In the DC area, I came to love not only the access to culture, but the ability to live in an urban location at the edge of where suburbs meet the country. I have quick access to pastoral nature, or I can go to a museum.

Charles: When did you start getting interested in writing poetry?

Michael: Poetry is an anomaly, a very strange thing. I got interested in writing poetry late in life. I remember specifically, it was around 2017. Growing up I was not a reader of poetry, and I was not thinking about writing it. I had written and published fiction, nonfiction, short stories, a novel, articles, blogs, but no poems.

But then something happened within my family. There was a health problem and a personal crisis. I was sitting on the deck one evening, and all of a sudden poetry came out.

I remember it was dusk one autumn evening and verse just started coming out of me. So I started writing poetry, and reading other people’s poems.

I gave one of my poems to somebody and they liked it. And from that point, I concentrated on writing verse. What I love about writing poetry was – and maybe this is a testament to my impatience – it’s contained. I don’t have the desire to spend a lot of time taking a set of ideas and crafting it for years into a novel. Poetry gives me an outlet to consider whatever is moving me at that moment, to scratch that itch and capture what I want to capture. Whether it's a childhood memory, or something theological, it could be anything. I love the freedom of being able to do that. And poetry has no rigid rules. Of course, there are certain kinds of poems with disciplined meter and rhyme, but you don’t have to follow that structure. For the most part, it's free reign and beauty is in the eye of the beholder. I love to follow the process of where an idea about a poem takes me.

Charles: What kinds of arts were you attracted to as a kid?

Michael: I was attracted to all the arts: painting, sculpture, drama, music. My talent, however, was in writing.

I don't have much musical talent, but music moves me more than any other art form, especially choral music, the combination of voices coming together. I just didn't have talent for it.

Charles: You weren't singing in school?

Michael: No, I don't have any singing talent.

In school, I excelled at writing. It was difficult for a while when the family business went bankrupt, my parents divorced and I wasn’t sure I could stay in a school with a great writing program. But my parents still managed to put me through private school. Although the writing that was valued in school was more of what I'd call modern American literature, not fantasy, not ancient themes, not the things I most enjoyed. So I didn't get a lot of traction with my teachers in those areas until later.

Charles: You already mentioned theological themes in your poems. Those are inadequate words to express what I’m after, and the word spiritual isn't much better. Would you talk a bit about your religious experience? How did you react to going to church as a kid? Were you raised in a Greek Orthodox Church?

Michael: Yes and no. From the moment I was born I wanted to know everything about everything. Mom and Dad weren't like that, but my mother fed my interest. She understood.

She got me a Golden Press Picture Bible, which is a very famous children's Bible. And I remember being up in my bedroom with it – this is before I knew about church, before anything else religious, I’d say around age four.

I opened up the Bible and the picture was of Jesus’s temptation in the wilderness. It had Jesus on a mountain top and the devil was circling him.

Something indescribable hit me in that moment about Jesus that has never left me. So my orientation to church was Christ first, and then being interested in church as the vehicle to finding out more about Christ. My family baptized me in the Greek Orthodox Church. But my grandmother was a Christian Scientist.

I attended both the Greek church but also Christian Science Sunday school. Christian Science is somewhat lined up with Gnosticism and the belief that the material reality is either an illusion or a secondary reality. They don’t adhere to the integration of spiritual and material as in Orthodoxy. Christian Science’s focus on the spiritual side gave me an appreciation for spiritual reality. And then later on, I came to reject some of the things that Christian Science espoused, but the foundation in spiritual reality remained.

Charles: Might not be a bad start.

Michael: Yeah, it wasn't. And for me, the existence of spiritual reality has never been in question. That sense was further accentuated when I encountered the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. When I read The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, there was a palpable sacramental and spiritual reality embedded in it. It’s not that he’d try to defend it or promote it. It was just there, and it lined up with me.

As for attending church, when my parents divorced and our family business went bankrupt, and other bad stuff happened, everything in our world fell apart and any tradition of going to church went with it. So I’d say I wasn't really raised in the church. But I was a seeker. I was reading on my own. And my grandmother was very spiritual. We would talk. I studied theologies, other religions on my own. And then I met a girl in college. She was a Roman Catholic. I went with her to church for four years. Afterwards, I met my wife, who later converted to Orthodoxy. When I met her she had been going to the Nazarene Church. I went there with her for ten years. So my church attendance has been very eclectic.

Charles: Was there any period where you were without faith or even atheistic?

Michael: No. Never,

Charles: So from age four on, you're exploring different things. But there's always a clear focus on Jesus?

Michael: There was, but I was very much a prodigal son at one point. My exploration didn't always take me to the light. But looking back, I always had that sense that there was a line I didn't cross.

I had a cousin who was a heroin addict. I knew criminals, some that aren't alive anymore. But I never crossed that line. Sometimes I was a witness to things. I didn't judge people's actions harshly because I knew sin should be seen as a sickness, and the church is a hospital for the sick, not a museum for the saints. When people get sick with sin and behave a certain way that doesn’t really speak to who they are. My cousin was a heroin addict. He succumbed to it. But I always knew he could be more than that if he wanted to.

Charles: When I was a kid, I saw the church as a very rigid museum-like place. Do you think seeing the Orthodox Church as very formal and rigid is common?

Michael: I do. For me, the reason the Orthodox Church was the last step in my church journey was because it had been sold to me when I was younger as a rigid place of superstitious, anti-intellectual thinking. The Christian Science tradition in my family brought with it a bit of intellectual snobbery. Christian Science, as I experienced it, sees itself as an intellectual religion and sees others as superstitious.

So the Orthodox Church was the last place I looked. One reason I got there was that in the mid-90s I happened to meet a man at the place I was working who was Greek Orthodox. He was very learned, very spiritual, and I pulled him aside one day. I said, “George, no offense, but you seem like a very learned and spiritual guy. What are you doing there?” He says, “I want you to get a couple books. Then we'll talk more. Go buy The Orthodox Church by Timothy Ware.”

I went to the bookstore and I saw, oh, well here's Timothy Ware, but there's this other guy named Metropolitan Kallistos Ware. Same guy, although I didn’t know that at the time. Anyway, I read the book. The first part is a history of the Church. The second part contains the theology. It floored me because it said what intuitively I had always believed. And so that began my journey to seek the Orthodox Church and then, through grace, I ended up meeting and spending about three years off and on with Metropolitan Kallistos.

I met him because the publisher of my book, Sacramental Living, happened to be one of his best friends. It was published by Eastern Christian Publications, which is owned by Jack Figel. Jack Figel is an Eastern Catholic. I was with him in Istanbul at the Phenar when he received an award from The Ecumenical Patriarch. Jack, Metropolitan Kallistos and a few others started a foundation dedicated to the Catholic-Orthodox dialogue. When Metropolitan Kallistos came to the States, he would stay with Jack.

Jack wanted to publish my book in serial form initially, in a magazine he was doing at the time. And I didn't know any better, but all of a sudden, my writing was being published alongside Metropolitan Kallistos’s article. I was a pigeon flying among the eagles.

Charles: And that book was how I first stumbled upon you. I loved how you talked about religion as a way of living. And connecting the physical reality of your body, of what you're doing in your daily routine, to spiritual life. Theologically, that is a central Orthodox way of approaching things, which you brought to life in your book. Your book is also very practical. I came to see you as playing a unique role in Orthodox Christianity today. I have friends who are fundamentalists, who see it as normal to put out their own writings to talk about religious themes. But that is not common for Orthodox laity. In fact, I don't know of anyone but you who is not an Orthodox Priest but has an Orthodox ministry.

Michael: Yes, I describe it that way, too. It's definitely unusual. I don't know if it's unique. I'm sure I'm not the only one. But perhaps I am unique in that I do that while running my own business which amounts to having another full-time job. I fell into it, frankly. And I've received a lot of grace to be able to do it.

Charles: And you're doing multiple things. I receive your email five days a week which has theological quotations that are grouped together thematically. And you also give adult classes, and you taught Sunday School for many years. You also deliver speeches, and you have a podcast with Ancient Faith Radio.

Michael: Yes, in my mind they’re all integrated. I transitioned to focusing on teaching adults because I became convinced that one has to reach adults to talk about how they're living their faith in their home. Then adults can pass that on to their kids, which then gets reinforced by Sunday school. But Sunday School alone can't do the job.

Charles: When I talk to Orthodox priests, I'll ask them if they know your newsletter and broadcasts. Sometimes I’m disappointed that they don't. That surprises me because I think these are some of the most exciting things going on in Orthodoxy in America. And I wonder if there's like a little bit of a turf issue there?

Michael: You know, my experience with priests has been the exact opposite. I easily have a dozen, probably two dozen, priests subscribing to my quotes of the day. And some of them are pretty high up. When I've been to gatherings with a bunch of priests and I'm sitting in the back, they'll wave me forward to participate. I find that the priests that do podcasts especially have a teaching spirit, a desire to share.

Charles: Well, why don't we turn and talk a little bit about some of your poetry. You know I like your poetry because I've written four pieces of music setting five of your poems.

Michael: I am grateful and find it amazing that you thought they were good enough to do that.

Charles: They are very inspiring. One of the things I'm trying to do in this newsletter is explore the process of creating art. So I’d like to hear you talk through the origins of some of the poems that appear on the album, Evlogía.

Why don't we start with the one about your cousin’s suicide, Blood, Blood, which is a very striking poem. When I set that to music, one of my friends told me not to publish it. She was very put off by it.

When some people are confronted with art that's about something very dark, they flee from it. They think it's weird. So, what possessed you to write a poem about that?

Michael: I'll tell you about that in a minute, but first I want to share something about being off-putting. I once belonged to a group of six people, including clergy and laity, who got together to talk occasionally. At one of our get togethers I read Blood, Blood. They all but recoiled. They did not receive it well at all. So I understand how it's off-putting, but obviously not to everybody.

The first line of the poem just hit me one day: “Blood, blood, humming, softly in its own tongue.”

I wasn't sitting around seeking the light. It just came out of the blue. So I went with it. But the origin of the poem, of course, was a real event that was quite grizzly.

When my cousin committed suicide, I wasn't at his house. He shot himself in the head at point blank range. So you can imagine what that made his room look like. When I arrived at his house the next morning – a house I more or less grew up in – his mother, for some reason, was intent on getting that room clean as soon as possible and insisted that I do that.

Charles: So he was already gone from the room.

Michael: Yes. Growing up a butcher's son, blood did not bother me much, but the room was, as you can imagine, a grizzly mess. I went into the room and shut the door behind me and locked it because I didn't want anyone to come in while I was cleaning it.

I remember in the room what hit me right away was the scripture passage about life in the blood. And that life in the blood was connected to a humming sound I could practically hear in the room. I wasn't put off by it. The hardest part wasn't the cleaning up. It was disposing of it. When I got everything in plastic bags and I drove around the corner of the Villanova hospital and threw it out, I felt like I was throwing him out. But anyway, that's where all that came from.

I've never shied away in my poetry from writing about dark things. But what I try to do is take that darkness of human suffering somewhere else. I think at least 95% of my dark poems end up in the light.

Nor do I consider myself a dark person. But if you're an artist, you go to dark places. It doesn't mean you live there, but you have to empathize and understand it. I'm keenly aware of people’s suffering. Whenever I put out daily quotes about suffering, I hear from many people right away. Suffering is universal.

Charles: When you go to a dark place, you either end up emerging from it or you don't. Some people get lost like your cousin. And some people come out of it. How do we make sense of that?

Michael: I don't have an answer. I don't think there's a rational way to understand why. I do firmly believe that my cousin, for whatever reason, made the choice to stay in the dark, but he was presented with so many opportunities to come out of it. He just couldn't get there. I don't know why.

I've experienced my own darkness. I've listened to other people's stories. I've seen enough to know – and I firmly believe without any hesitation – that God is present in the darkness, just like at the very beginning of the Bible. And on Mount Sinai, when he appeared in the darkness because the light was too much for people. And sometimes you need the dark in order to see the light. That opportunity is always there in the darkness.

Why some choose not to take the opportunity? I don’t know. If you read Chronicles of Narnia, at the end, the last battle, the dwarfs couldn't hear Aslan's voice. I can't rationalize that. I don't think we're supposed to.

Charles: Deliverance is another poem about dealing with darkness. If I had to guess, I would guess that this was about someone you knew and wanted to help. The point of the poem is that pushing someone in the right direction doesn’t generally work.

Michael: I wrote that poem when my wife was very ill. Her illness was baffling the doctors. I believe that everything, every disorder we have, at its root is spiritual, whether it manifests in what we call physical, your body, mind, and soul are connected as one. So I was trying to guide her towards solutions and treatment, but nothing was working. I had a little bit of a feeling of helplessness.

It was beyond my capabilities and beyond any quick fix, whether a quick fix in the medical world, or in the church world. Some people say, oh, just pray, as if there's almost a mathematical certainty about how once you pray you get the outcome you want. It doesn’t work that way. My deep desire to help didn’t fix the problem.

Charles: There is a recognition moment in the poem, I would call it an epiphany, where you recognize it’s counterproductive to push too hard, and more generally, that the end doesn't justify the means. That to help people in need you must avoid excessive actions or insistence. You have to let them find their own way. And that was the thing about the poem that attracted me.

Michael: You have to let them find their own way. Let people be. That's something I’ve learned, which I’m conscious of in any relationship, whether marital, parent, friend, business co-workers… let people be. When we respect their freedom, we are respecting the power that God gives them to choose. But be there to help. Let them have the freedom to blossom, to grow, to change, even if they're making choices that are bad, because you don't know how God's leading them.

Charles: One of your poems I set to music in Evlogía I would describe as an epic.

Michael: Which is Climbing Ladders, which you described to me as Dr. Faustopoulos. And I agree. It is a Faustian journey.

Charles: I like the versions of Faust where there's redemption in the end. In your poem someone begins on the wrong path and then finds a way to get back on the right path. In Orthodoxy, people use ladders quite a bit as metaphors for growing spiritually. And of course, we celebrate the writing about that by St. John of the Ladder. Did that influence you? It’s a long poem, too, and it reminded me in its length and repetitive structure a little bit of the lyrics to American Pie.

Michael: I do like telling stories through poems, bordering on an epic in terms of length.

Charles: And it is great storytelling. The vocalist, Demetris Kehagias, told me that when he was rehearsing it, his mom was enraptured, waiting to see how it would turn out.

Michael: That's nice to hear. I think it works as a story. The narrative is gripping. A lot of modern poetry is written in a free verse style. It can be effective at communicating what a person is feeling. I've used it that way. I like poems sometimes to just tell a story. And yes, that poem was inspired by an icon of St. John of the Ladder, especially that big gaping mouth at the end.

Even though his ladder is a ziggurat, technically, but then we also think of Jacob’s ladder. And we use the ladder as a metaphor for Christ climbing down the ladder to earth, his mother, Theotokos. I was also thinking about the ladder of success and how many people I know regret giving into too much ambition at the expense of other things.

Charles: Yes, I feel that sometimes.

Michael: Me, too. After all, in the Greek culture, ambition and success are highly valued, right? It’s a double-edged sword. How it ends up depends on how you wield the tool. Again, we are talking about going from dark things to light.

I mentioned earlier my parents were both divorced twice, all this nonsense happened as I was growing up, bankruptcy, all sorts of stuff. But that gave me a strong desire to be a checked-in husband and father. Way before I even was one. I was determined to revolve my life around those roles. And it also made me sensitive when I was in the corporate world listening to people's stories who had regrets. Matter of fact, when I decided I was working for this company, my daughter wasn't born yet, but my wife was pregnant. I sent an email one morning to the head of the unit I worked in. He was pretty high up. He was an early bird. And I said, I want to start telecommuting, which at the time was unheard of.

He called me to his office, slammed the door. I thought he was going to cuss me out. And then he told me his life story, how he messed up his family. He got a second chance and he applauded what I was doing.

So Climbing Ladders begins with the first ladder that was climbed, the more attractive one. That was all about succumbing to the ladder of success, but paying the price. And then moving to the second ladder.

Charles: There are many things in that poem that are immediately understandable, but not easy to explain. Let me give you an example. One ladder made of steel, one made of wood. It's like it's immediately explicable that the steel is in some sense the obvious, easy answer. So how did you come up with that? Because that's not, of course, St. John's ladder, or any of the other ones you mentioned.

Michael: Well, the wood is connected to bearing our cross and the related idea that we have to go through pain and suffering. Why steel? If I were to go to Home Depot and buy a ladder to get up on myself, I’d want something strong like steel.

Charles: I think the use of two ladders is a new metaphor. Have you ever seen it before?

Michael: No, I haven't. When writing poems, I like to conflate and change and try new angles. Not trying to be novel, per se, but when it hits me, being willing to go in a direction, not knowing necessarily where it's going to go, not being bound by what I started with. When it hit me to talk about two ladders, I just went with it. It works.

I was surprised you chose it to set to music, because of the length. I wanted to cut it.

Charles: I tried to cut it when setting it to music, but I found that I couldn't. It's uncuttable because every line is indispensable to the story.

Michael: Well, that's good to hear because I wasn't sure about that. Matter of fact, even to this day, even though I've had like fifty or so published poems, I don't think of myself as a poet. I'm a bit insecure about what I produce. I don't know until someone else sees value in it if it's any good.

But that's okay. I don't mind that. Never thinking I've arrived keeps me sharp. It's a devil on my shoulder, but I'm saying, you're not going to derail me, and there's value in what you're saying as you're trying to derail me. If that makes sense.

Charles: Your poems show that humility, I’d say. And that's something that was very visible to me and definitely was part of the attraction to wanting to climb into those poems with you. It’s funny that here we are having lunch together and meeting for the first time, but I have felt for a long time that I know you from your writings.

Michael: I was telling my wife the same. We never met in person, but we've been talking and collaborating for what, a decade? I don't know. Something like that.

Charles: Yes, it's been a long time. It's kind of crazy, but I think part of it too is that this belief that the material world in some sense is kind of an illusion. I just felt like, well, I know the real Michael. It would be nice to meet the flesh and blood version.

Let me change the topic. It’s a particular challenge, I think, to combine faith and art. It can come off badly and be preachy. And then there are questions about whether religious norms can get in the way of artistic sensibilities. I'm wondering if you'd share some thoughts or advice about that?

Michael: First of all, there is a saying, and I don't know who said it: if it's true, then it's Christian. That’s my view, and not the reverse idea, that something has to be Christian to be true.

Any artistic expression that is about truth and beauty is worthwhile. I try to ignore anything that whispers in my brain that is telling me about boundaries, about what not to think, because one of the things I've not liked about some of the art that is branded Christian is that it is too consciously counter-cultural. I think culture shapes everything. People of faith should be creating art when they are moved by something, and they should not impose artificial boundaries on that process.

Charles: One of my upcoming newsletters is about what I call the “Beauty Paradox,” which expresses a point of view almost identical to what you just said. I couldn’t agree more with you.

Michael: I think my process tends to be free of any artificial boundaries partly because I run my own business. I'm not beholden to anybody for fundraising or whatever. I just let the inspiration come.

If it doesn't come, I don't get worked up about that. I start from a place of inspiration, and I go with it. After inspiration, I do some crafting and then I look for external validation. I'm never doing anything just on my own. I'm always going through some gates of accountability.

Charles: Well, count me among the happy gatekeepers. I look forward to seeing lots more of your poetry and setting more of it to music in the future. Thanks again for taking the time.

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)